Atlantic City’s tourism district is home to New Jersey’s biggest needle exchange. The Oasis Drop In Center on Tennessee Avenue gives out thousands more needles than are returned each week. The streets near hotels, casinos, restaurants and parks are strewn with orange caps and used needles. First responders say they are as afraid of accidental needle-sticks as of gunshots. And some parents won’t let their children use the city’s main public library, just a block from the needle exchange.

Needle exchanges help reduce the spread of diseases such as Hepatitis C and AIDS through intravenous-drug use. The cost of treating people with Hepatitis C alone in the United States reached $6.5 billion in 2011, far outweighing the cost of harm reduction programs. But syringe service or access programs often face opposition, particularly when used needles become a public health hazard.

The South Jersey Aids Alliance, which runs Atlantic City’s Oasis Drop In Center on Tennessee Avenue, knows that more than 200,000 of its needles do not come back each year. Under its current budget cycle, the Alliance is spending $75,000 on its syringe service program, with just $6,000 or 8 percent of that going to syringe disposal. That could change, however. “Recent information suggests that the increased retrieval of syringes will be a priority moving forward,” wrote the Alliance’s Chief Executive Carol Harney in an emailed response to Route 40 questions last month. (Harney declined an interview and did not respond to follow-up questions.)

Other New Jersey needle exchanges have already taken steps to improve their needle recovery rate. “We need to make sure that the syringes in the streets are not visible, or there are less of them, otherwise people are going to use that as a reason to attack the program,” said Alicia Parker, who runs the Hyacinth needle exchange program in Jersey City. Making sure that program participants understand this has helped improve Hyacinth’s needle-recovery rate to 59 percent this year through August, from 47 percent last year. Parker says program participants also know that if they do not bring enough needles back, they will not get so many new needles. In another effort to increase safe disposal, Jersey City needle-exchange participants receive one-quart sharps containers for used needles, and are encouraged to bring those containers back to the exchange program, Parker said.

Used needles were lying outside the former Taj Mahal human resources office in August this year.

Needle exchanges are backed by the U.S. government and World Health Organization (WHO) because more than a quarter of new AIDS cases in the United States are linked to I.V.-drug use. But disposing of used needles is expensive and – when not done properly – hazardous. Earlier this year, Atlantic City firefighters tackled a fire in a house strewn with drugs and needles. An empty building next to The Walk outlets became a temporary shelter for intravenous drug users that artists from the nearby Noyes Arts Garage cleared up (it was later boarded up by the site owner). Brown Park was filled with needle users and their debris until a renovation project this year. And the entrance way to the human resources office at the former Taj Mahal was last month littered with used needles.

The issue of safe disposal for drug needles near Atlantic City’s Oasis Drop In Center is particularly important because it is in an area with heavy foot traffic, close to the Boardwalk in the tourism district and close to community resources such as the library. The exchange program is unpopular with local business owners, according to notes from the city’s Boardwalk Committee last month. The center is also just one block away from the soon-to-open “Tennessee Avenue Renaissance”, a pedestrian-and-bike-focused development experiment featuring an outdoor beer garden. (A spokesman for the project’s developers declined to comment on the issue of needle disposal in the area). While relocating the center is one obvious solution, it would be costly and take time. There are other ways of reducing the number of used needles in Atlantic City’s streets.

Other needle exchanges around the country have made sure the area near their sites is not littered with used syringes by sending staff out to collect needles, officials told us. This is considered a best practice, although it has never been required in New Jersey, a NJ Department of Health spokeswoman said. South Jersey Aids Alliance’s Oasis Drop In Center and Paterson’s Point of Hope Syringe Access Program began their first street sweeps this month, the spokeswoman said.

Cutting Littered Needle Numbers

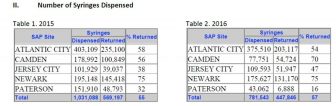

Paterson and other cities in New Jersey – which operate much smaller needle exchange programs than Atlantic City’s – also have a poor recovery rate, but last year they either improved returns or significantly curbed needle distribution. In Atlantic City, the Oasis Drop In Center doled out slightly fewer syringes last year, but its return-rate worsened to just 54 percent. On an average week last year, the center gave out 7,221 needles and 3,899 were not returned for proper disposal. When the Oasis Drop In Center performed its first street sweep this month, employees brought back 880 needles–about a quarter of those that go missing each week–NJ DoH spokeswoman Nicole Kirgan said.

There has been a sharp decline in New Jersey HIV cases linked to intravenous-drug use since needle exchanges began. Programs such as the one operated by Atlantic City’s South Jersey Aids Alliance are funded by the federal government, and funneled through state health departments that have responsibility for overseeing the exchange programs. South Jersey Aids Alliance received $1.2 million this year in federal funding, making it one of the nation’s biggest federally-funded HIV prevention programs (see table below).

How Many Needles Should Be Distributed?

The WHO recommends about 200 clean needles be provided each year to an I.V.-drug user. It is not clear how many users in Atlantic City are registered and use the needle-exchange on a regular basis, but the Oasis needle numbers seem high even when taking into account the greater Atlantic County area and tourist numbers. The Drop In Center last year handed out 375,510 syringes, more than 1,000 a day or about 10 for each city resident. The center gave out more than twice the number of needles distributed by a similar program in Newark, New Jersey’s largest city, with a population seven times Atlantic City’s. The South Jersey Aids Alliance says about 100 people come into its Atlantic City drop-in center–which also provides showers, condoms, personal care kits and other services–each day. It is not clear how many needles are going out of the center each day on a per-user basis, but Route 40 was shown video of a user leaving the center this summer with a backpack brim-filled with new syringes in neat elastic-band-wrapped bundles. (The South Jersey Aids Alliance’s Harney did not respond to further questions about the street sweep or the center’s plans to increase its needle-recovery rate).

A notice on the window of the Oasis Drop In Center in Atlantic City.

Some officials said I.V.-drug users prefer to drop used needles because if they are stopped by police they fear the used needles would be viewed as drug paraphernalia and be cause for arrest. A spokesman for Atlantic City’s police department said the city would not arrest people who are registered with the needle exchange (New Jersey gives its needle-exchange participants cards to carry upon registration) just for having needles on their person. The police would, however, arrest a needle-exchange participant who has needles and drugs on them. Needle exchange programs are responsible for educating users about their rights and responsibilities. It is something of a technicality, but the federal funding that pays for needle exchange programs is not to be used for illegal drug injection.

Some cities in Europe, Canada and Australia have implemented ‘safe shooting galleries’ where users can go to inject drugs in sites with nurses and overdose antidotes, out of the public’s way. The first such U.S. site is in the works in Seattle, although there are already efforts to ban it. It is not clear how such sites might help to reduce litter related to drug use, however. Unless they are open around the clock, users (including homeless) congregate near the sites waiting for opening hours.

Overcoming Tourism District Challenges

One of the goals of the Atlantic City Tourism District, created by Gov. Chris Christie in 2011, was to improve cleanliness in the city. The district encompasses the bulk of the city’s business areas and it is overseen with varying degrees of effectiveness by overlapping city and state authorities. Until this year, the state’s Casino Reinvestment Development Authority (CRDA) was in charge of planning in the area without a zoning plan.

Tom Gilbert, commander of the tourism district, was given responsibility for leading policing in the area in 2011. But recently, amid a battle between the state and the city’s police and fire departments over cost and job cuts necessary to improve Atlantic City’s finances, Gilbert has worked behind the scenes. Except at special events (he was awarded the 2017 Spirit of Hospitality Award by CRDA and was spotted at the air show last month) he’s been out of view.

Gilbert said he is aware of the issue of discarded needles in the tourism district’s streets, particularly around the Oasis Drop In Center on South Tennessee Avenue. “We’re asking and encouraging the staff at the South Jersey Aids Alliance to work with us in encouraging the best possible return rate of syringes from their current location where they’re situated,” said Gilbert.

CRDA helped the John Brooks Recovery Center move some facilities away from its tourism district site on Pacific Avenue in Atlantic City. When asked whether he is looking at relocating the Oasis Drop In Center, Gilbert said, “I think we’re going to have to get those issues before all the right people to determine what the best course of action is.”

Other cities have also installed more sharps containers near needle-exchange sites, some needle exchanges such as this one in California even hand out cards with a map of safe outdoor drop boxes when they issue new needles, and others like San Francisco have considered installing them in parks. Gilbert said that the South Jersey Aids Alliance is best-placed to answer questions about installing more drop boxes in the city (Harney did not respond to further questions this month).

A needle discarded in a landscaped corner near the Oasis Drop In Center.

The scale of Atlantic City’s needle exchange program and HIV services undercuts the arguments of Governor Chris Christie and the state’s takeover officials, that because the city has fewer than 40,000 full-time residents it needs to cut its emergency services payroll.

The city’s police and fire officials have been fighting against this since the takeover began in November, noting that Atlantic City might have a low year-round population but it faces unique challenges with its urban tourist population, unlike other shore towns.

“We have had members stuck before by dirty needles and that and the follow-up treatment and stigma of contracting a horrible disease is honestly as scary if not scarier than being shot,” said Matt Rogers, president of the Atlantic City police union. New issues related to injury compensation since the state takeover add to that stress, he said. “Now with the added stress of the unknown ‘case by case’ basis in which we are ‘entitled’ to injury compensation it is far too much of an added burden put on the men and women of this department.”

Atlantic City firefighters’ union President Bill DiLorenzo said city firefighters have also been stuck by discarded needles, which have become a real hazard particularly when tackling fires in abandoned buildings.

Gilbert acknowledged there are many different entities involved in helping Atlantic City balance its tourism industry with the number of drug-users drawn to the city. He did not respond to a direct question about the challenges facing the city’s police amid the state’s efforts to cut the force’s budget. “We’ve moved in the right direction to bring everybody to the table to try and look at this holistically rather than in silos,” he said. “We have to have the right partners interfacing with each other.”

Gilbert said the needle disposal problem is part of wider issues related to addiction that he is trying to address in partnership with Atlanticare, John Brooks, the South Jersey Aids Alliance, the ACPD and others. Those groups are in the middle of assessing data on the scale of Atlantic City’s addiction issues, Gilbert said, adding that he is not sure when the assessment will be complete.

Top 10 HIV Prevention Projects Ranked By Grant Awarded:

| Name of HIV Prevention Activities Grant Recipient | City | State | Award Amount |

|---|---|---|---|

| HIV ALLIANCE | EUGENE | OR | $6,876,705 |

| HIV ALLIANCE | EUGENE | OR | $2,249,400 |

| MULTNOMAH, COUNTY OF | PORTLAND | OR | $1,614,972 |

| KING, COUNTY OF | SEATTLE | WA | $1,566,079 |

| AIDS ALABAMA, INC. | BIRMINGHAM | AL | $1,511,277 |

| SOUTH JERSEY AIDS ALLIANCE INC | ATLANTIC CITY | NJ | $1,251,000 |

| UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO, THE | CHICAGO | IL | $1,100,000 |

| SHELBY, COUNTY OF | MEMPHIS | TN | $973,800 |

| PRINCE GEORGE, COUNTY OF | UPPER MARLBORO | MD | $945,000 |

| UNITED WAY OF MIDDLE TENNESSEE, INC. | NASHVILLE | TN | $879,056 |