Laurie Egrie is walking down the hallway of Sovereign Avenue School carrying a cardboard box filled with odd little balls and popsicle sticks with notelets stuck to them, and she’s wedged an easel-sized writing pad under one arm. The corridor is half dark. School let out 15 minutes ago.

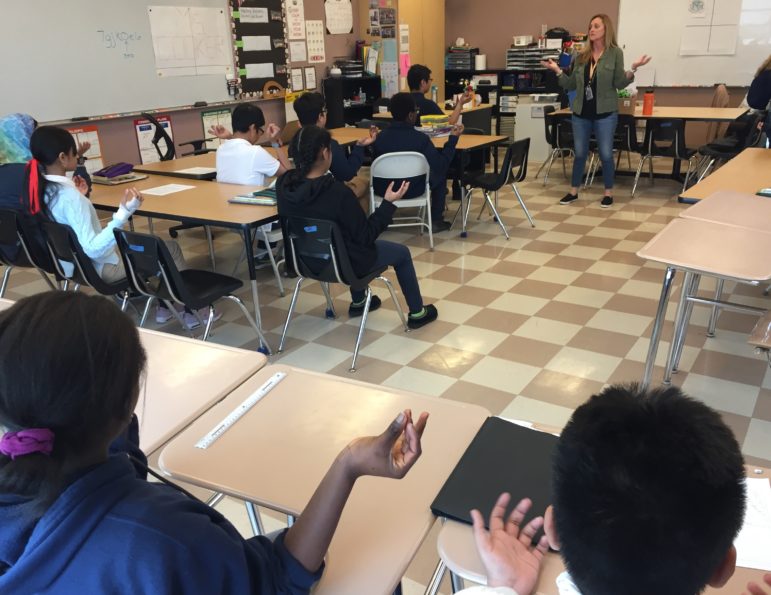

A student appears and asks Egrie, “Can I help you?” They juggle the writing pad and box and together maneuver the load through a classroom door. Inside, a dozen or so students sit. The teacher pauses in the middle of a math class. Many of the students move their hands so their palms are flat on their legs under their desks. Their knees are at 90 degrees and their feet are flat on the floor, pointed straight ahead of them. The movement seems regimented but involuntary. Their gaze is on Egrie as she walks in.

In the next 90 minutes, Egrie will teach 160 kids how to breathe.

This is the first year that two Atlantic City schools – Richmond Avenue and Sovereign Avenue – have tried out a “mindful movement” program as part of their after-school enrichment classes. Egrie and a colleague at Richmond Avenue School, Linda Coyle*, spend just 10 minutes in multiple classrooms every Monday and Wednesday that after-school is in session. The schedule is so intense, sometimes they have to work to control their own breathing before they enter each classroom.

Teaching more than 100 Atlantic City school kids how to calm down in 10 minutes sounds kind of crazy, I remark. But that’s before I witness how eager the students are for a few minutes to, well, just breathe.

In each classroom we walk into, it’s as if the students – and their teachers – get a fresh start when they see Egrie. Faces turn to her and a palpable calm spreads through the room. Shoulders relax and jaws unclench. It would be hard to tell it is almost 4pm and everyone has been in school since 8.15am.

In one classroom, a teacher is proud to tell Egrie that her students have been practicing leading their classmates through breathing exercises each day. She asks two students to demonstrate with the class’s own Hoberman spheres (the odd little balls from Egrie’s box). The students stand at the front of the class and as they expand the balls, everyone in the room inhales, and as the balls contract, everyone exhales, for ten deep breaths. “They don’t even have to count!” the teacher says.

The 10-minute sessions are not just about breathing, but rather the whole concept of mindfulness and socio-emotional learning. Mindfulness may sound like mumbo jumbo to non-yogis. But as Egrie talks to the students, it is clear they are all in.

Students in one class preparing for state testing run through a half-dozen techniques they can use to tackle any panic or anxiety that might be brought on by a difficult test question. In a class of fourth-graders, Egrie leads students through a visualization. They imagine the scent of their favorite flower as they breathe in and create a secret garden in their mind, to which they can escape when they need a break from the present. Another group learns a technique called five-finger breathing, tracing a finger up and down their opposite palm to help control their breath. Sometimes Egrie teaches about the brain and the science of mindfulness. Other times, the 10-minute lesson is about how to focus.

Egrie, a yoga teacher as well as a reading specialist and former fourth-grade teacher, says she wasn’t sure herself how it would work when the academic year began. When the program ran last year and the year before, it was structured differently, with more time and space for yoga. But in its current iteration, dozens more Atlantic City students can learn mindfulness techiques each week.

“Of course, there were a few resisters who laughed in the beginning,” Egrie says. “It was beautiful to watch them eventually take the practices on.”

Students now stop Egrie in the hallway to tell her how they are using the practices, she says. Teachers that initially objected to having their lessons interrupted have also come on board.

Egrie started bringing yoga into the classroom when she was a fourth-grade teacher and starting her own training to be a yoga instructor.

“I would practice on my students and during state testing time would have them meditate to focus and do yoga in the afternoon to relieve stress,” she says. “I began to notice how often I used these tools throughout my day and how focused and calm my students became.

“I knew it was something missing in schools. It changed the way I showed up for my students and handled the many stressors, challenges, changes and successes throughout the day. My kids were calm because I was calm.”

After Egrie talked to Mike Bird, district director (and fellow yogi), about how much her students were benefiting from yoga and meditation, Bird, Egrie and others worked to introduce Atlantic City School District’s first yoga program in the 2016-2017 academic year. It was a more time-intensive (and teacher-intensive) program, involving a morning class as well as 20-minute afternoon sessions.

The following year, the program ran from 7am to 8am. Students had time to journal, as well as practice yoga and meditate. But starting early made it difficult for many students to attend regularly.

This year the program was tested as part of after-school sessions at Sovereign Avenue School by Egrie, with the support of her principal, Medina Peyton, and at Richmond Avenue School by Coyle, with the support of her principal, Shelley Williams.

The program is set to expand to more schools in the district during summer school this year.

*Coyle has been an essential part of the program from the beginning, Egrie says. “I couldn’t do what I do without her.”

Thank you so much. Beautifully written. You have told the story of your boys at Christmas time after it happened. I loved hearing it again. Our work in the community is happening ❤🕉 ❤ thank for who you and Bill are in this community.