This story was funded by a grant from the Center for Cooperative Media at Montclair State University as part of its In the Shadow of Liberty – Immigration in New Jersey project.

There was a time a little over a decade ago when Claudia Velasquez was in the seventh grade and she didn’t speak any English. She is now attaching paper on a flip-board, preparing to give a class in English, in the same red-brick Pleasantville school on Washington Avenue where she learned the language.

“It was very hard,” said Velasquez, remembering how it felt to try and absorb school lessons in a foreign language. She said she felt lucky to be in Pleasantville, where there was a bilingual program and she and her brother were not the only new foreign students. Within two years, she entered Pleasantville High School and went on to college and graduate studies.

Pleasantville’s Washington Avenue Elementary School has more than 400 students from Kindergarten through fifth grade in a variety of different bilingual classes.

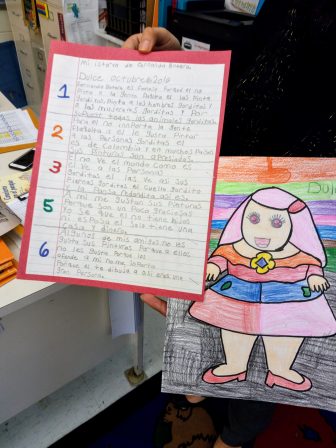

For thousands of parents and children, the Washington Avenue Elementary School has been – and still is – a haven. The school has scrubby grass and neglected trees outside, but the hallways inside are filled with brightly-colored displays of students’ work in Spanish and English. Behind closed doors, children are taking turns to answer questions in both languages. Outside the principal’s office, a bilingual secretary is explaining school-trip instructions to a Spanish-speaking parent.

But the school’s teachers and others in the state are worried about the future. Each year in New Jersey there are over two thousand new students who need bilingual teaching or English-as-a-second-language (ESL) classes and there is a shortage of teachers. School funding is under national and state-wide scrutiny. And, as political rhetoric around immigration becomes ever more heated, bilingual and ESL teachers are tasked with bridging gaps between communities that seem to be moving further apart.

The United States Constitution and Supreme Court precedent protect immigrant children’s right to education, regardless of their legal status. But recent headlines and rumors of immigration raids and deportations are creating an environment of stress and anxiety that is seeping into schoolrooms.

“We are working with children and if parents are afraid to come to their schools to report crises such as abuse or serious illnesses, then schools cannot offer support and assistance,” explains Kim O’Brien, who teaches English as a second language in Somers Point. The bayside town has about 900 children in its school district, about 5 percent of whom were classed as English-language learners last year. Schools have relationships with many organizations that provide important services, O’Brien explained, adding that teachers want parents to be partners in their children’s learning to maximize their access to a quality education. “When parents’ basic needs are met and distractions are minimized, they can better focus on reading to their children and being involved at school,” added O’Brien, who went back to teaching ESL last year after a stint teaching Spanish because enrollment of limited-English speakers in the district increased.

Fear among immigrants – both legal and illegal – is spreading as President Trump takes a hard line on immigration. Although federal courts have blocked some of his immigration policy orders, border crossings into the United States by documented and undocumented migrants are down since he took office, The Washington Post has reported. And although there are some protections against the deportation of parents, in the first half of last year alone, the United States removed 11,542 parents of U.S.-born children. Teachers say that worry about parents or other relatives being deported is adding to stress for immigrant students, some of whom are already dealing with trauma after leaving difficult circumstances in their home country.

Cynthia Ruiz Cooper, the principal of Pleasantville’s Washington Avenue school, said that there was a lot of concern in the school on the day after the election and some students went to the guidance counselor’s office. “We reassured them that they were safe,” she said. “When you’re in school, you’re safe.”

But even before the White House immigration rhetoric became more hostile to immigrants, the American Civil Liberties Union of New Jersey discovered some school districts were blocking entry to immigrant children. The ACLU-NJ in 2006 found that one in four New Jersey public schools were illegally requesting Social Security numbers or asking other questions to reveal the immigration status of children seeking to enroll in school. The ACLU-NJ went on to file multiple lawsuits against various districts that did not change their enrollment policies to fall in line with federal and state requirements. And as recently as last year the organization sued certain districts in Atlantic, Bergen, Hudson and Middlesex counties (the lawsuits were eventually settled).

Alexander Shalom, a senior staff attorney for the ACLU-NJ who worked on the school-district lawsuits, said he worries that injecting more fear into the immigrant community could have an impact on school attendance. “We know that people are clearly suffering a lot of trauma and we have heard anecdotally of people staying away from places of employment,” he said. “I think the fear is that that will trickle over to the school environment, which obviously would be really detrimental.”

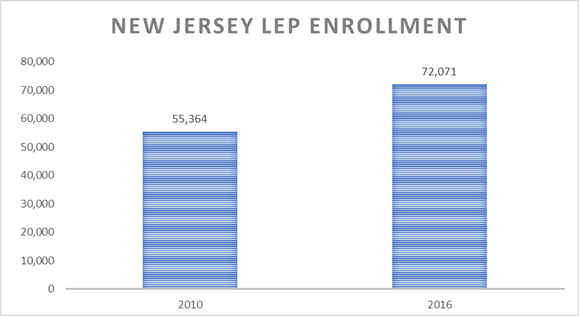

Data from the New Jersey Department of Education

There are more than 72,000 children in New Jersey schools who receive some form of ESL or bilingual teaching. The state records the number of students who are classified by their district as Limited English Proficient (LEP). That number is a rough proxy for newly-arrived immigrant school children, sometimes called newcomers or port-of-entry students, as well as for U.S.-born children of immigrant parents who still speak another language at home. Across New Jersey, the number of students classified as speaking limited English has increased by almost one third since 2010, according to data from the state’s Department of Education. Over the same period, total student enrollment in New Jersey is flat.

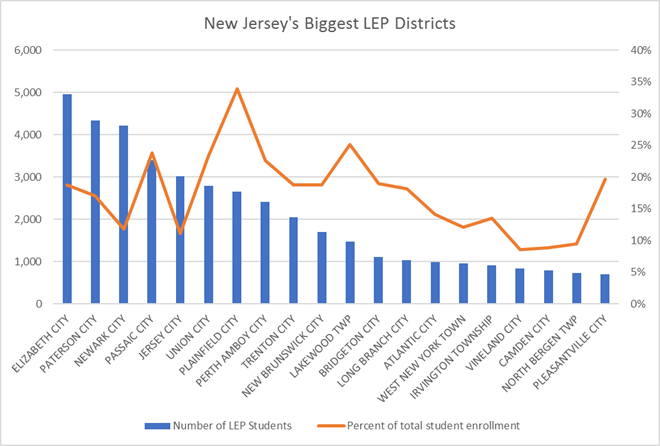

In South Jersey, where there are more small school districts, there are some areas with no schoolchildren receiving extra English classes. But South Jersey also includes school districts such as Vineland, Bridgeton, Atlantic City and Pleasantville, that rank among New Jersey’s largest by the size of their limited-English-speaking enrollment.

Immigration has been a feature of South Jersey life for decades. The low-wage tourism industry has drawn immigrants from around the world and while the local economy boomed and busted, one constant was the schools. Teaching English to immigrant children helped connect the diverse – and sometimes insulated – communities in South Jersey, where the population is sparser and more spread out, and where school districts are smaller than those in the north of the state.

One of the districts sued by the ACLU-NJ last year was Atlantic County’s Port Republic. It’s a tiny district of just 118 students and none that are recorded as being limited-English speakers. The district’s superintendent did not respond to requests for comment. Several teachers interviewed by Route 40 said that in many districts, there are likely officials who are unaware that it is against the law to request registration documents that require a legal immigration status. Although the rules governing ESL and bilingual teaching are written out in the state’s administrative code, smaller districts may be less aware of those rules, these teachers said.

Data from the New Jersey Department of Education.

“Sometimes you don’t know that you’re doing something wrong until someone comes in and tells you and if you’re in a small district you can get overlooked,” said JoAnne Negrin, the supervisor of ESL, world languages, bilingual education and performing arts in the Vineland school district. “That’s a challenge in New Jersey more than in other states that have regional or county districts – we’re just all over the map in terms of what the level of knowledge is.” Negrin works with NJTESOL/NJBE, a state-wide organization for ESL and bilingual teachers, to improve awareness of the administrative code and all the programs and support available to English-language learners and their teachers.

Somers Point’s O’Brien said that, for instance, it can be hard to keep track of which school documents are available in multiple languages and make sure that all teachers and staff know how to find those documents. Perhaps more professional development for support staff, as well as teachers, could help, she said.

More training for support staff in school districts with immigrant students might also help school districts avoid the problems uncovered by the ACLU-NJ. Just last week during kindergarten registration in Ventnor, a small district of 700 students where about one in 20 students was identified last year as needing English-language help, staff members handling enrollment were going back and forth between the registration table and the school office to check which documents they could accept.

Larger districts already have bilingual assistants. Pleasantville’s Ruiz Cooper described her bilingual secretary as “a godsend” who helps build the relationship between the school and parents. And in Atlantic City, another large district with multiple bilingual staff on hand, parents spoke in glowing terms of the school’s efforts to communicate with them.

On a warm, sunny Spring afternoon outside Atlantic City’s Richmond Avenue elementary school, parents including women in saris and men in tupi caps waited to collect their children. Shilpi Begum said she arrived from Dubai late last year (she’s originally from Bangladesh) and the school was quick to enroll her child and she felt it was welcoming to immigrants like herself, who speak little English. But Anahi Gonzalez, from Oaxaca, Mexico, said she is worried about the “general political environment.” “There is a lot of stress,” she said, comforting the three-month old in her arms. Still, she said she thinks the school’s teachers are understanding of the children’s worries and concern about family members. “They are doing what they can to help,” she said.

Funding

There is a difference between the types of classes that are on offer to immigrant students in large districts and small districts. That is because New Jersey uses a school-funding formula that pays for teaching based on the needs of students in the district. But the difference goes beyond that formula. Districts like Pleasantville have seen a large population of mostly Spanish-speaking children go through the school system over decades. That means the district, where currently one in five students are limited-English speakers, has been able to develop a range of different class types for those students and it can also offer more services for parents, because there is a concentrated group of English-language learners all in one school. Meanwhile, in smaller districts, students may have nothing more than the state-mandated one period of ESL teaching.

School work written in Spanish by a second-grader in the dual language program at Pleasantville’s Washington Avenue Elementary School.

Although schools with a need for bilingual education automatically receive funding to support those students – which can include funding and supporting their teachers – a shortage of teachers means it can still be hard to find and keep teachers in a bilingual program, explained Vineland’s Negrin. At the same time, funding for additional services such as translating documents and teaching parents is not as clear a case as funding for teachers. As state legislators discuss the school-funding formula, provisions for English-language learners have come up repeatedly.

There are other issues too. Many of the state’s English-language learners are from low-income families. Depending on their immigration status, they may not qualify for assistance such as uniform vouchers, and Pleasantville’s Ruiz Cooper says often her teaching staff step in with clothing donations and other help for students that need it. Not having computers at home can also put these children at a disadvantage. Districts including Ventnor have worked with their local public library to make sure there are computers in the children’s section that are ready to run with the same academic programs used by the school.

Teachers are already dealing with these challenges and in many cases are providing solutions that have a direct impact on the lives of English-language learners. Students such as Pleasantville’s Velasquez are a testament to that impact. Velasquez, who began as an ESL student and now teaches in a dual-language class, where children switch every two weeks between learning in Spanish and learning in English, says there was one individual teacher who had a personal impact on her life.

Velasquez attributes her success to her first teacher in the United States, Renee Gensamer, who now coordinates ESL and bilingual programs across the Pleasantville school district. Gensamer also taught Velasquez’ brother, who is now finishing college and working in a bank. “From the moment we came to the country, she never gave up on us,” Velasquez said. “Our test scores were low, but not because we couldn’t – because of the language,” she explains.

At times in college, Velasquez would struggle with writing essays. To get through it, she would think back on the confidence that Gensamer had in her. When she started substitute teaching after college, she called Gensamer to tell her about it and it was Gensamer who persuaded her to get additional certification so she could work as a bilingual teacher. “I’m really happy for the experience and the opportunity to give back,” Velasquez said.