Sometime around lunch on Monday of this week, Bill Terrigino of 227 Metropolitan Avenue stood outside gardening in one of the two yards on either side of his home in the South Inlet neighborhood of Atlantic City.

Close readers of this space may remember Bill as the oft-chronicled inhabitant of a charming, cedar-sided Victorian house, nearly 110 years old, that has the interesting fate of being located directly across the street from the Revel casino hotel resort, the second-tallest building in the state of New Jersey and the most notorious casino flop in the history of Atlantic City and probably of the world, which sat about 50 feet to the west of Bill’s geraniums,* humming like a spaceship that was running out of electricity.

Revel’s owner, an eccentric millionaire named Glenn Straub, had set that coming Wednesday–about 48 hours in the future–as the deadline for what’s been described as a grand reopening, a “soft” opening, a “real soft” opening and a “flaccid” flop (the local press corps has some bros in it). Which made Bill’s neighborhood once again a subject of some media interest.

Bill, who’d worked as a banquet waiter at the Golden Nugget back in the 80s, had lived with his family in the Inlet since the early 1990s, and had been in his house well over a decade when work began on the gargantuan Revel, and the South Inlet was turned into the biggest construction site New Jersey. A cement-mixing machine sent clouds of fine gray sand spinning up Metropolitan and heavy equipment swung over Bill’s bedroom and the big gray wall of Revel’s eastern facade rose across the street.

As the completed Revel overshadowed Bill’s house, and much of the rest of the South Inlet, Bill had remained remarkably upbeat about the megaresort and the effects it would have on the city, and his particular section of it, but in 2014, two bankruptcies later, the property was closed. In April 2015, Straub bought it for five cents on the dollar and began issuing bold statements about his plans for the property, and the city itself. But the first year and a half of Straub’s ownership had seen little in the way of tangible progress to reopen the casino.

At the time of the sale Straub was squabbling with owners of the property’s power plant, who were threatening to cut the power and let the property molder in the South Jersey summer, rapidly approaching. Bill had a message for the new owner. A sign hung from his front porch announced “Glenn Straub Welcome to the Neighborhood” in big bubble letters. Then below that, “Free Electricity” in cursive script.

Some sixteen months later, Bill had a different message for the two reporters outside his house. “If you see Glenn Straub, punch him in the fucking nose,” he joked.

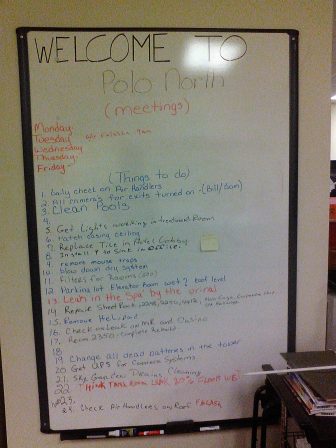

As luck would have it, about ten minutes later–through no journalistic chops of my own–I happened to be standing in Glenn Straub’s war room on the first floor of his surreal property, with the enigmatic Mr. Straub a few feet away, looking at his to-do list, which contained, among other interesting chores, “9. remove mouse traps,” and “15. Remove Helipad.”

Straub presumably had a lot to do to get the big building tidied up for the guests who were theoretically set to begin arriving in 48 hours, but he seemed unhurried, if also exhausted.

He is long-limbed and slightly bow-legged and red-haired and tanned. He plays polo and tennis, if I understood him correctly. And he has a busted collarbone he refuses to have fixed. I was told if he wears a teeshirt—which he sometimes does around the office—you can see it sticking out.

Straub, an inveterate bargain-hunter, took the time to secure some free publicity. Someone had handed him a ham salad in a black plastic serving tray of the kind you might get at an airport deli. Straub had assembled the salad–i.e. added the ham to the greens–dressed it, then promptly abandoned lunch altogether and led us on a tour of the property.

Glenn Straub’s uneaten ham salad

Apart from the stray mousetraps and residual helipad, a group of young scalawags from Exit 63 had penetrated the Revel’s security perimeter and avidly set about photographing themselves engaged in all manner of acrobatic hijinks on the Revel’s notorious “Escalator of Death.” Straub said their endgame had been the pearl at the Revel’s top but the trespassers had been nabbed after dicking around in the lobby for some undetermined period of time.

Straub seemed only mildly resentful of this interruption to his day, and oddly enough the creative reuse of the lobby didn’t sound unlike Straub’s own vision for the space, which included some kind of mountain-climbing course with a zip-line that would allow patrons to plunge down many flights of empty space, to the delight of gamblers on the other side of the lobby glass.

But the course had yet to be completed (“They couldn’t get it done for me by June 15”) or even started, and at present the lobby contained a shop-vac and a nearby mop that appeared to have been hastily abandoned by whomever’d used them last. Elsewhere were other signs Straub might not meet his Wednesday deadline.

The back door, which led to the war room where Straub spent his days, was propped open by a traffic cone, and when my colleague rang the bell, the person who opened it was Straub himself. Likewise a side door used by visiting dignitaries was propped with a gas cannister.

Apart from Straub’s office assistants–at the office in their activewear–there were remarkably few people of any kind inside the Revel. The doors connecting the lobby to the porte cochere I think is the technical term, were still blocked with plywood to keep out the relentless volumes of sand blowing off the beach. In this big outside space there were perhaps three workers, not including Straub. Two of them were suspiciously well-dressed teens who appeared to have strayed into the building while looking for a surf shop, and for a second I thought maybe the tresspassers from the night before had been conscripted to move piles of stone from one side of the porch to another, but Straub said one of them was the son of the Revel’s spa operator.

But soon they would begin pouring concrete, Straub said. It wouldn’t take them long once they got started. The space would hold tennis courts, white-sand beaches, and concerts for 8,000 people. Maybe at the same time. Plans for palm trees were being revisited amid concerns over the aforementioned wind, which was relentless. In fact the only time Straub seemed dismayed was at the mention of this wind (“It’s always windy”, he said). But he was committed to incorporating nature into the future Revel experience. And the view from the porte cochere was in fact delightful. You can actually see, of all things, the Atlantic Ocean, which now that a row of dunes stretch from Ventnor to Absecon Inlet, you can no longer do from the world-famous Atlantic City Boardwalk itself. Which is yet another reason to forgo the town’s non-gaming amenities in favor of sitting in front of a slot machine. You can actually see, from certain select vantages, the fucking water.

But where were we.

On Tuesday, 24 hours before the theoretical relaunch, Straub led a delegation from city hall on a tour of the property, which still looked to me like a set from one of those History Channel documentaries about what New York City would look like if humanity was wiped out by an interstellar plague.

The group of city officials–including Mayor Don Guardian and Councilmen Mary Small and Kaleem Shabazz–congealed on Oriental Avenue near the traffic-cone entrance, wearing little white hardhats, then they disappeared into the building. By the time they emerged on the porte cochere, a group of reporters and civilians (in about equal number) had arrived to observe the spectacle from the boardwalk. The reporters entered the porte cochere to confront Straub, and he launched into another impromptu press conference, returning with them to the Boardwalk to discuss his plans for the beach.

I could not, in decency, join this press conference, as I’m not a credentialed journalist, nor, technically, even a grownup, not that Straub would have minded. But I openly eavesdropped. And in the little bit I overheard, Straub talked about his plans to have horseback riding on the beach. He dared anyone to ride a horse into the Atlantic Ocean, and not fall off, and not laugh his ass off, it sounded like.

But pretty soon, Straub had shed the reporters and disappeared back into the building with the mayor and co. for what I imagine was some kind of reality check about whether or not Straub had jumped through the necessary regulatory hoops. Or even started.

Straub suggested casually that meeting the reopening deadline would depend on, “how late we work tonight.” But there were other more ominous signs of the informality of the Straub Administration, and the fact that the problems facing the building might not be surmountable by Straub’s own considerable work ethic. Apart from the general post-apocalyptic vibe of the place, there seemed to be no way to make a reservation. A Facebook page for the Revel appeared to not have been updated in two years. If there was a website for the hotel, I couldn’t find it. And there appeared to be no staff. Then there was the question of the bathrooms.

The sewer company, in a dispute with Straub, had cut off service, and for some time you could flush the toilets in the Revel, but the sewerage was not carried off to the treatment plant. And many months’ worth of festering turds, many of them Glenn Straub’s presumably, had built up in the pipes in and around the Revel, which pipes had been blocked by the sewer company until Straub paid his bill. They were described as like a rubber air bag and about the size of a basketball–the sewer plugs, not Straub’s turds–but either way they needed to be removed before guests could use the Revel’s native toilets.

There were port-o-potties inside, but these were hardly suitable accomodation for guests of a luxury resort hotel. Ditto the tap water, which was currently not potable. But Revel didn’t have a certificate of occupancy from the city, so Dom Perignon could have flowed from its faucets, and Straub still couldn’t check in guests. Not that there appeared to be staff on hand to check-in guests anyway. The logistics of elevator inspection alone made an opening anytime this week mathematically improbable.

Not that any of this would have mattered, to me anyway, if you could get a drink, or sip one in your room by yourself. I would happily pitch a tent in the porte cochere and sit there with a six pack, but there were no liquor permits. So apparently that was forbidden as well.

When Straub reemerged from the hotel onto Oriental Avenue, where the reporters had gathered, he led his guests on a tour of the power plant, which is, if anything, even more impressive and surreal than the Revel itself—built to provide power not only to a second, at present imaginary, Revel hotel tower but also to all the ancillary retail, residential and back-of-house development that was presumed to accompany the successful $2.4 billion megaresort. But none of that has materialized either. At the moment, the South Inlet is as barren and uninhabited as it’s ever been. And the plant operates at a fraction of its capacity.

Straub visibly loves the power plant and lit up as he led the tour of the big facility, with its brightly colored tubes and impressive generators. But when the guests left and it was just Straub and the reporters, he seemed tired and sat down on the curb to collect himself. The reporters sat down dutifully beside him (no danger of inconveniencing any stray pedestrians) and the press conference continued from the sidewalk. I love a good sidewalk confab, but this seemed like the big weird maraschino cherry on the surreal hot fudge sundae of the preceding 24 hours.

I think it was during the power-plant phase of the tour, when the sewage disposal truck showed up to drain off the excess feculence, presumably, from the port-o- potties. It seemed too orchestrated to be true.

The reporters dutifully listened to Straub’s spiel, then went back to their offices and told their readers, as politely as they could, that there was no way in hell the Revel was going to open the next day.

A shop-vac sits in the Revel lobby, Monday, June 13, 2016.

It’s easy enough for congenital jackasses in the media, who’ve never built a goddamn thing in their lives–I’m thinking of myself here–to get glib on the subject of Glenn Straub and his big weird hotel. The plans he has floated for the property have veered so wildly–from cryogenic ski slopes to Syrian refugees and genius towers–that it’s hard to imagine those ideas originated in the same consciousness, or that that consciousness existed in the head of a very sane or stable human being.

Steve Wynn–who is legally blind–may have put his elbow through a Picasso–but the press at least was required, in ridiculing Wynn, to observe that he’d owned the Picasso in the first place. The most revealing portrait we have on record of Glenn Straub is the image of him sweeping up a cup of spilled coffee and Splenda with the receipt from an Atlantic City McDonald’s. He was eating a ham salad and had just come from a Trump rally for Christ’s sake. This is a media jackass’s definition of a target-rich environment.

But he bought the Revel for five cents on the dollar. So far his major achievement has been in wresting control of the power plant from its previous, usurious, owners–not as flashy as the grand-opening of a casino, but Straub added value to the property in that one act. He could probably sell the Revel tomorrow for $50 million more than he paid for it, but it seems he’d rather go to work each day in the control room of an empty hotel in one of the most notoriously depressing neighborhoods in the state of New Jersey. And there’s something weirdly noble in that.

It occurred to me that Glenn Straub and Bill Terrigino have more in common than it might seem at first glance. For one thing, they’re about the same age (70, give or take) and they both sort of putter around their properties, tending to various chores, with various degrees of efficacy. Each of them could, should he choose, spend his days somewhere more comfortable–Florida, probably, in each guy’s case–but instead they hang out in the same weird little section of Absecon Island. Glenn’s control center and Bill’s front door are about 400 feet apart as the crow flies.

A plugged sewer main leading from the Revel, June 15, 2016

On Wednesday morning, the day of the alleged soft opening, Straub was not immediately on hand. I’d ridden my bike up Pacific Avenue on the off chance that the 13-floor endurance bike track Straub had described to me 48 hours earlier would be open, but the gate to the self-parking lot was still closed.

A ring of the buzzer by traffic cone entrance produced not Straub but an assistant who said he would be unavailable, huddled with his lawyer all day. Out front, one of the other office workers–still in her activewear–had donned a pair of rubber gloves and was personally polishing the railings of the porte cochere. We weren’t allowed inside, she said. Mr. Straub would be releasing details of the situation on Friday.

The good news for Straub, I suppose, was that if there were any other disappointed guests, I certainly didn’t see any. On Metropolitan Avenue, I met a couple from Tennessee who’d decided to take a stroll around the big glass building, but they seemed a) unaware it was a shuttered casino or b) that anything unusual had been scheduled that week. They’d been drawn in by its weird energy.

The press corps had thinned considerably, and the delegation from city hall was nowhere to be found. But over on New Jersey Avenue, there were some exciting developments. A crew from the sewage company had gathered beside a manhole, awaiting final OK to remove the stopper they’d been using to block his pipes.

The seemed genuinely concerned to see what would happen when they got the order to execute Operation Super Colon Blow on several-month’s worth of Revel wastewater. Would the airbags be swept out with the tide? The foreman, in his thirty-year career, had never shut off the sewage to a casino before. It was unprecedented.

But by 11:00 a.m. they’d still not received the final go-ahead and decided to cut out for lunch. Last I saw, the stoppers were still in place.

***

In September 2015 Angelou Economics, a consultant retained by the Atlantic County Improvement Authority, released a study that noted the region’s over-reliance on a single industry–gambling-related tourism–for jobs and investment, a reliance that was unusual and not conducive to economic health. “The extent of the dominance of gaming tourism in Atlantic County to the detriment of all other clusters is uncommon, and should be regarded as a serious long-term threat to future economic prosperity.”

But the problem is that a lot of vested interests are vested in ensuring that industry retains its local dominance. They have a lot of resources and don’t seem particularly interested in fostering the growth of other industries.

Revel was supposed to break the Atlantic City mold by being a resort first and a casino second, which, incidentally, is a version of the task Atlantic City is facing itself. Glenn Straub, who seems to think of casinos as a secondary amenity when he thinks of them at all, was either the vanguard of the revolution or the canary in the coal mine. Either way, that’s the reason I’ve been rooting for him.

***

There’s a line in Nick Paumgarten’s New Yorker essay on the Revel (“The Death and Life of Atlantic City,” September 2015) that captured our ongoing confusion about Atlantic City’s problems, and the extent of the casino industry’s involvement in creating them. Apropos of Revel’s eccentric new owner, Paumgarten noted the many zany schemes emanating from the beach block of New Jersey and Metropolitan Avenues. But that wasn’t such a bad thing, perhaps, Paumgarten mused. “If not for zany schemes, Atlantic City would still be a sand dune.”

The New Yorker editors liked it so much they used it as the pull-quote in the print version of their story. But as a counterfactual, it struck me as incorrect on two simultaneous fronts. After all, the New Jersey shore is remarkably built-out, as they say, from Sandy Hook to Cape May. One remaining stretch of undeveloped land, curiously, is the piece of Absecon Island that was the subject of Paumgarten’s story. And those beach blocks aren’t some isolated backwater. They’re very near the epicenter of a sophisticated industry that’s attracted capital and visitors from every corner of the globe.

The South Inlet isn’t the Rub’ al Khali. It’s just been land-banked for 37 years.

***

Stray construction equipment, Bill T’s house in the upper right corner.

Bill Terrigino had had some trouble with the city inspectors since the last time I’d talked to him. He’d been made to cut down the grape vines that adorned his house, a rare source of joy in a neighborhood that’s almost statutorily required to represent despair and surrender to the residents of South Jersey.

Bill said he felt targeted. The South Inlet overfloweth with eyesores, from the pile of rusting I-beams two lots over from his house to the “TRUMP” sign at the top of the Taj Mahal casino, which is missing a letter. Why him? A certain “Inspector Lou” was a particular villain. It was one more thing he had in common with his millionaire neighbor, who was fighting with everyone from the DGE to the CRDA to the CCC.

The past few days had been a p.r. disaster for Glenn Straub. The more interesting question was whether he gave a particular shit. My suspicion, based on flimsy experience, was that he did not. Maybe he wasn’t hardwired to be sensitive to such problems–a real asset in A.C.

It occurred to me that Bill had suggested a kind of p.r. stunt that might rehabilitate Mr. Straub in the eyes of locals. It took place right after he, Bill, suggested I punch Glenn in the face.

Bill had a motorcycle–a Harley, I think–that had been destroyed when someone made an ill-advised K-turn in front of his house during the Revel’s construction. And he had a replacment bike in front of his house at present. Straub too was a bike enthusiast, Bill said. And he played polo. Bill proposed a game of motorcycle polo between himself and Mr. Straub at a time of the latter’s choosing. The game was banned, but the beach blocks of Vermont Avenue offered an appealing venue.

I’ll start feeling optimistic if someday these two old pirates pull that off.

* I don’t really know if they’re geraniums or what.