Imagining Atlantic City after the Fall

This story was originally published via Medium in February 2015.

SOMETIMES IN THE SOUL’S DARK NIGHT or when I just have nothing better to do, I like to go trawling through old books or magazine articles about Atlantic City to find the passages where the town is compared to an aging prostitute.

These happen a) about as often as you’d expect and b) more often than you might like, particularly if the town in question happens to be your home town, as Atlantic City happens to be mine.

Take, for instance, the New York magazine review of the great Louis Malle filmAtlantic City (1981), which notes the filmmakers have captured the town at the moment of its civic rebirth, i.e, “its transformation from a tattered old tart to a sparkling young whore.” There’s the Bloomberg review of Jonathan Van Meter’s delightful The Last Good Time (2003), a biography of the nightclub impresario Paul “Skinny” D’Amato, wherein the reviewer states that, although the public face of Atlantic City might be Miss America, behind closed doors, Atlantic City was, “always a whore.”

Nelson Johnson—whose valuable Boardwalk Empire (2002) brought the story of Atlantic City’s long accommodation with the vice industries to so many Americans—uses variations on “prostitute” fourteen times and “whore” another eight in his book. Sometimes these are straightforward assertions of fact (“Everyone knew the resort was a sanctuary for out-of-town whores,”), but other times there’s something sweeping and editorial that can strike partial observers like me as a little tawdry: Atlantic City in 1974 was, “a broken-down old whore scratching for customers,” for instance. Or, the failure of the casino referendum was, “a kick in the ass to a tired old whore who had lost her charm.” And so on.

Details from this lurid little anthology taxied to the front of my brain a few weeks ago when I drove out to the site of the Revel Casino Hotel, in the northeast corner of Atlantic City, to survey the progress achieved in this town through thirty-eight-plus years of legal casino gambling. Atlantic City had never seemed like Miss America to me, but it had never seemed like a whore either. This town, and in particular its South Inlet neighborhood, atop whose ruins the Revel was built, is the closest thing to an ancestral village I have—maybe the closest to an ancestral village it’s possible for anyone to have in a place as synonymous with strip malls and real estate subdivisions as New Jersey.

My parents grew up in the 1950s and 60s on the beach block of Vermont Avenue, about two hundred yards east of what is now the Revel’s front door. A whole array of grandparents and step-grandparents and aunts and uncles and cousins lived in scattered apartments across the Inlet at mid-century, when the neighborhood was an aging but nevertheless still lively mix of boarding houses and apartments and motels, all squeezed into an elbow of the famous Atlantic City Boardwalk—a kind of working-class residential community with a tourism overlay.

My grandmother was a Leeds, from the family that first settled Atlantic City in the early nineteenth century. Jeremiah Leeds, a distant ancestor, had built a cabin on Absecon Island—the top third of which is now Atlantic City—as early as the 1780s and supposedly spent the last fifty years of his life on “Beach Field,” near what is now the corner of Massachusetts and Atlantic Avenues in the Inlet. Millicent Leeds, Jeremiah’s wife, operated the first boarding house on the island. When the railroad was built in the 1850s, James Leeds, John Leeds, Andrew Leeds and Judith Leeds were among the handful of residents. A Chalkley Leeds was the first mayor. Robert Leeds, the first post-master.

For years it was this kind of ritual whenever I came home to South Jersey, to drive out to the Inlet to view the wreckage of the old neighborhood that so much of my family had called home. I had an uncle who’d worked for the housing authority, and sometimes we would sit and contemplate the paradox of the beachfront parking lot that now stood where various beloved childhood landmarks once existed. Then, as now, the Inlet was a disorienting mix of vacant land—some of it vacant for decades—and for-sale signs, derelict apartment buildings that sat crumbling in the glow of casino-hotels valued in the hundreds of millions, if not billions, of dollars, oceanfront ghetto and rolling grassland that wouldn’t seem too out of place in South Dakota.

The neighborhood remained largely, surreally undeveloped through the first thirty years of Atlantic City’s experiment with legal gambling, even as casinos were slapped up, knocked down, and slapped up again just a few blocks south. The arrival of the Showboat (1987) had blotted out the remnants of States Avenue, an especially beloved Inlet boulevard, but with few immediate side-effects. The adjacent block contained — contains — a combination parking lot-vacant lot. Donald Trump’s Taj Mahal and its non-metaphorical white elephants arrived in 1990, but it too was a self-contained fantasyland, as it was designed to be, with little spillover. Much of the surrounding land was essentially the same as it had been in the 1970s—block after block of faintly undulating grassland, the outlines of old driveways, faint outlines of old alleyways, rows of telephone polls left standing though the houses they connected had long ago been carted away, boarding houses knocked down or falling apart on their own authority.

By the 1990s the urban grassland was so integrated into the pattern of life in the city that footpaths had been etched across it by pedestrians. There was an old guy who used to go out there and practice his golf game in broad daylight. I had this recurring dream where I lived in one of the old Victorian guesthouses left on an otherwise abandoned block. The lights had gone out and everywhere the island was reverting to the state of nature, an image strongly suggested by actual neighborhood conditions. Like Atlantic City itself it was tough and sad and strange and, in its weird way, beautiful.

There was one house on Metropolitan Avenue that always seemed particularly appealing. It had lawn furniture, and a lifeguard boat that had been turned into a planter and filled with flowers. A pirate flag flew from the balcony, and a sign out front said, “One old hippie and one flower child live here.” Around it on every side, vacant lots stretched for blocks. I imagined sitting on the porch in the evenings and watching the sun go down across the prairie.

“This is waterfront resort land, the scarcest land in America,” Palley said more recently. “To use it for housing was just insane.

***

ALL ATLANTIC CITY STORIES contemplate how to fix Atlantic City. All Atlantic City stories to some extent concern what went wrong with the place. Maybe because my life has coincided so precisely with the Atlantic City’s post-referendum trajectory—I was born the year gambing was legalized—it’s hard for me to imagine what a successful version of this town was ever supposed to look like.

Atlantic City has been hovering in a kind of fugue state between conspicuous death and some promised, hypothetical rebirth my entire life. There’s a moment in the Louis Malle film — nearly all the scenes of which contain a bulldozer, or a vacant lot, or a crumbling apartment building, or a crumbling apartment building surrounded by bulldozers, about to be turned into a vacant lot — where the famous crooner Robert Goulet, wearing an unbelievable leisure suit, serenades the lobby of the Frank Sinatra Wing of the Atlantic City Medical Center. “Glad to see you’re born again,” he sings, as the patients shuffle about in their robes. “Atlantic City, my old friend, you sure came through.” The long great litany of false Atlantic City messiahs, from Steve Wynn to Merv Griffin to Donald Trump, has its spiritual origins in that scene and Robert Goulet’s hair.

There’s a school of thought that says no people—and certainly no members of the poor or working classes—should actually live in Atlantic City. The principle of highest-and-best use requires that real estate of such inherent preciousness—beachside property within a few hours’ drive of both New York City and Philadelphia—should be reserved for development of a certain grandeur and dignity, even if that means large sections of the city have sat fallow for decades, and much of the development that did take place has all the grandeur and dignity of some of Saddam Hussein’s classier palaces.

This urban-planning philosophy—Atlantic City as reprobate Disneyland—was given its most candid expression probably by Reese Palley, an art dealer and all-around man of the world, who got himself in “trouble,” in his own words, in the 1960s for saying the solution to Atlantic City’s problems was, “a bulldozer six blocks wide.”

“This is waterfront resort land, the scarcest land in America,” Palley said more recently. “To use it for housing was just insane. They could have built anything they wanted. They could have turned it into a dreamland.”

“Now it needs a bulldozer twelve blocks wide.”

But from the vantage point of the Inlet—from Vermont Avenue, or Rhode Island Avenue, or New Jersey Avenue—such comments, the wistful musings of civic plutocrats, can seem a little disconnected from historical realities. However politically impractical they may have sounded, the Inlet was one place the bulldozers did come through, forty years ago, yet the neighborhood remains a kind of dreamland, though not the kind Reese Palley was talking about.

***

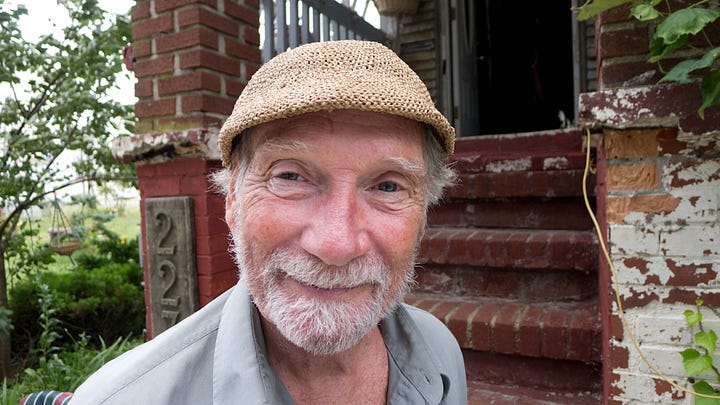

BILL AND CATHY TERRIGINO BOUGHT the house at 227 Metropolitan Avenue on November 13, 1993, Bill’s birthday. They paid cash for the property. Native Philadelphians, they’d been coming to Atlantic City since childhood. Bill’s parents—whose house once stood on land now occupied by the 47-story Revel casino—spent their honeymoon in the resort town and then returned faithfully every summer afterward. Bill himself spent his childhood summers running up and down Metropolitan Avenue not knowing that one day he’d own a house and raise three kids on the same block. But, unlike him, the kids hadn’t had to make the trek back to South Philly on Sunday afternoons, he told me, rather proudly, last fall.

Before the move to the Inlet, the Terriginos had lived on Arkansas Avenue, a little more than a mile down the beach. Bill was in no way opposed to casinos, having worked in the industry since 1984 when he got a job as a banquet waiter at the Golden Nugget, then owned by Steve Wynn (“The Wynns were nice people. I waited on Steve,” he said), and he worked in the industry for thirty years, through multiple changes of ownership, before the Golden Nugget property, known finally as the Atlantic Club, was closed in 2014.

In the pre-Revel years, the Terriginos nearest casino neighbor was the Showboat, five blocks south on States Avenue. At night, from their front porch, they could hear the music from the Steel Pier, and out their front door the ruins of the Inlet opened before them in all their South Dakotan glory. In the mornings they watched the sun come up over the Atlantic Ocean, visible from an upper-story window, and in the evenings they watched it set again over the prairie.

“It was so magnificent, from one end to the other,” Cathy said. “What a great backyard.”

When I first knocked on their door, completely unannounced, in June 2010, construction on the Revel had been underway for a little over two years. The temperature was 101° on the mainland. The wind, blowing about forty-five miles per hour up Metropolitan Avenue, made the heat bearable but carried with it a fine gray sand from the concrete mixer at the end of the street. The Terrigino property stuck out not so much because of the great charm the house possesses, but because whoever lived there appeared to be enjoying doing so, in contradiction to the traditional narrative that the Inlet was so crime-and-poverty infested that the only residents left were those who couldn’t escape.

The house was covered in vines, and in the side yard a lifeguard boat sat filled with flowers. A pirate flag hung from a second-floor balcony. In fact the whole house had the air of a pirate ship that had run aground in the middle of a residential street. But, of course, it wasn’t a residential street. For forty years it had been part of the big urban prairie of the South Inlet, and now it was the biggest construction site in the state of New Jersey.

Even as the 47-story Revel grew up about outside his front door, construction equipment dangling above his head, Bill Terrigino said he’d had his doubts about the project. Development of the state-of-the-art mega resort, Atlantic City’s first new casino property in a decade, had been undertaken initially by Morgan Stanley—ninety percent owner of Revel Entertainment—and the start of construction coincided not only with the beginning of the worst financial crisis to hit the country since the Great Depression, but also with the end of Atlantic City’s regional casino monopoly. New gambling venues were opening in Pennsylvania, Maryland and Delaware, and casino revenues in Atlantic City were begining their multi-year, ongoing slide. All across town, properties were cutting expenses, reducing staff. Why would Morgan Stanley (“They’re from the big casino, Wall Street,” Bill said) be investing?

“Early on I gave it a song,” Bill said. “The song was from Ray Charles, calledBorn to Lose.”

“Now I’m living next door to Revel without a Cause.”

Morgan Stanley spent about $1 billion on the Revel—whose imposing glass facade sits about fifty-five feet across Metropolitan Avenue from the Terrigino’s 100-year old cedar-shingled Victorian—before selling its stake in the project in April 2010 at a calamitous loss. Four hundred workers were laid off as the project ran out of money. The number of planned hotel rooms was cut in half. A crane collapsed and injured someone on the ground. The roof caught fire. In February 2011, in a bid to save the foundering project, the State of New Jersey committed $260 million in exchange for a share of future revenues. The same month, a consortium of hedge funds provided another $1.5 billion in bridge financing.

Meanwhile, Metropolitan Avenue was torn up, more than once. A section of Connecticut Avenue was widened and re-christened “Revel Boulevard.” At one point during the construction, Bill said, acknowledging that it sounded crazy, the neighborhood pigeons disappeared and have not been seen since. He offered a ten-dollar reward for evidence of pigeon activity on his block. During Hurricane Sandy, as network news channels were running encomiums about the late city and sections of the Boardwalk were shown floating down Atlantic Avenue, Metropolitan Avenue didn’t even flood, Bill said, due to the industrial-strength storm drains installed as part of the casino infrastructure.

When the tower was being topped off, the construction crew had a party to celebrate, and someone knocked on the door to invite Bill. “It’s like you work here,” he said they told him. “You’re on the job site. We have cranes going over top of your head. We want you to come, have a drink with us, eat some of the barbecue.”

The kids had given Bill the pirate flag that flew from his balcony, and the workers used to give directions based off the “Pirate House.” At one point, one of them offered to buy the flag.

“It’s not for sale,” Bill announced. “But I will donate it.”

The next time he saw it, the flag was flying above the casino.

A scaled-back version of the Revel opened in April 2012 and lost $35 million and $37 million in its first two quarters. In June 2014, two bankruptcies later, the owners announced they would close the property at summer’s end if a suitable buyer wasn’t found. At a bankruptcy auction last October, a month after the property went dark, Brookfield Asset Management, a Canadian company that specializes in distressed assets, won the rights to buy the Revel for $110 million — less than five percent of the development costs.

When I talked to Bill late last summer, a few days after the Revel had closed, he seemed upbeat, despite being out-of-work, about to turn seventy in a city with 8,000 other newly unemployed casino workers, and living across the street from an obsolete mega-resort that looked like that thing that keeps ice zombies out of Westeros in Game of Thrones. We sat on his (still very windy) front porch and he chatted with the workers doing various maintenance chores around the darkened building.

“As this gray wall grew up around us,” he said, “it just…It’s like a sundial. At three o’clock, you’re in the shade.”

“Will you stay?” I asked.

“Yeah, it’s my home,” he said. “My children were basically raised in this house — two children. As long as they need a home base, I’ll just keep the place.”

Touring the grounds around the house, he showed me the barbecue grill where the young men of the neighborhood — some of them not so young — would sometimes roast marshmallows. He said he had a modest income — social security and a small pension — but his costs were low — taxes and utilities. He seemed more concerned for the younger generation.

At one point, the mailman came down the street and yelled something to Bill about motorcycles. Evidently people’s satellite navigation systems still brought cars up Metropolitan Avenue in a mistaken effort to lead them to the Revel’s front door via the Boardwalk. One driver, opting to reverse back up the street rather than make a K-turn, had destroyed Bill’s Harley. Allstate had provided a replacement however, so: happy ending.

There was really only one moment when Bill sounded angry or dismayed by the situation—the scale of the ineptitude that had so grotesquely transformed his neighborhood while failing even to ensure its livelihood. It was when he was talking about the scarecrow.

From a pile of disused Boardwalk boards salvaged from a dumpster, Bill had built a scarecrow, dressed it in a Hawaiian shirt, put a surfboard under its arm and named it “Metro,” and before long tourists were posing for pictures with Metro, a symptom, Bill said, of something deeply wrong in a town that thought of itself as an entertainment capital, that his garbage art should have become a photo-op.

“It’s a big gray wall,” he said. “You probably have penitentiaries that have more character. Moyamensing Prison in Philadelphia? That has more character than this place. That’s what it boils down to.

“It’s hard to get into, off the Boardwalk. It’s uninviting. At night time, it’sforeboding—at both ends. It’s dark, dingy and frightening.”

***

THE CUSTOMARY ATLANTIC CITY LAMENT is that the enormous wealth generated by the casinos has failed to lift the town from its poverty. The paradox of beachfront ghetto side-by-side with billion dollar resort properties is explained away as a failure of trickle-down economics, a reassuring failure, at least, in that it makes the pleasant assumption that the town’s residents and its principal industry are fighting on the same side.

When they are not straightforwardly racist (and they frequently are), explanations for this failure tend to circle around some vague nexus of political incompetence and anonymous greed. Nelson Johnson, writing last September in The New York Times (whore-count: twenty-two and holding), said Atlantic City’s legacy of squandered opportunities was due to a culture of “political bossism” dating back to the Nucky Johnson-era, and on the failures of political imagination usual under such circumstances (“City Hall is where innovative ideas go to die”). George Anastasia, writing in Politico, said there was something in the DNA of Atlantic City—which he calls “The Big Hustle” (prostitution reference?)—that had made the town’s failure more or less inevitable.

“Even during its halcyon days, Atlantic City was an enterprise built around blue smoke and mirrors,” he wrote. But instead of keeping itself “dolled up” (yes) as Las Vegas had sensibly done, Atlantic City instead “smears on a little red lipstick and shrugs” (I’m counting it). Reese Palley, in a similar spirit, called the “stupidity” (he doesn’t say whose) “mind-boggling” and blamed the city’s residents for having squandered so many “God-given” opportunities. “There’s no chance of building additional tourist attractions in a dying city that’s whistling past the graveyard,” he said.

But it seems strange—or maybe not—that even at this late date one rarely hears that maybe the casinos themselves might bear some responsibility for Atlantic City’s failure to be a town at least, that maybe, as Reese Palley at least had the candor to suggest, the industry and the community were incompatible in some fundamental way from the beginning, that maybe the reason the town never succeeded is because it wasn’t supposed to.

***

THERE MIGHT HAVE BEEN A TIME WHEN THE CASINO INDUSTRY had some interest in developing the town in which its gambling halls were required, by law, to operate, but soon the casinos became, essentially, factories, highly efficient machines designed to draw in visitors, encourage them to lose their money at a pre-determined rate, and then spit them back onto the Atlantic City Expressway as frictionlessly as possible. The physical fact of the casinos—grim, windowless bunkers decked out in Christmas lights—cut the town off from its beach and Boardwalk, which were, after all, the reasons for its existence in the first place. Each of the casinos has its accompanying parking complex and bus depot, to facilitate the coming and going of the main by-product of its manufacturing activity—which is broke strung-out tourists—and this set of buildings, even grimmer, windowless bunkers but without the Christmas lights, forms another imposing line down Pacific Avenue, further cutting off the city from the beach. What in any normal town would be a main retail drag in Atlantic City is a grim canyon of parking garages where only the most subterranean industries—titty bars, cash-for-gold outlets—seem to feel welcome.

Those of us who remember the early days of gambling, when the Boardwalk was still considered iconic, have watched with horror as the casinos have extended their hegemony across this historic expanse, mostly in the form of loudspeakers that spray, at the ears of unlucky pedestrians, music of a volume and type seemingly culled from the CIA manual on enhanced interrogation. Likewise the beach itself, which I thought of as a sacrosanct natural resource, the way New Yorkers think of Central Park, has been encroached on by a series of tacky beach bars and protective dunes. If you survive the gauntlet of bus depots, parking lots, valet parking stations, drive ways and daunting cement casino exteriors, you must still clear these last two barriers before you even begin to sense the presence of the Atlantic Ocean, or of any colors or surfaces inoffensive to nature.

Even where the casinos have not impinged directly, physically on the composition of the town, the shadow of their potential can be felt where the prospect of some future development has meant that beach-front land was more valuable left sitting vacant for years than it was divided out and developed piecemeal. Depending on whom you believe, the Revel developers paid between $70 million and $94 million for the land beneath their defunct casino. The paradox of of the burned-out Inlet seems less paradoxical when you consider that much of the land was vacant not because of its proximity to racial minorities, or poor people or criminals, but because it was held by speculators waiting to cash out on the next mega-resort.

And in this way Bill and Cathy Terrigino’s story becomes less a quirky, isolated local-interest story and more an emblem of post-referendum Atlantic City: the casino industry never developed the town, because it was never in its interest to do so.

***

IN 2012, WILL DOIG, a journalist who covers urban-planning and policy issues, wrote an essay in Salon comparing the fate of Atlantic City with that of its neighbor up the coast, Asbury Park, and pondering some vision of the town not so grounded perhaps in the mono-crop economy of monopolistic legal gambling (“Casinos aren’t the Future”). Asbury Park and Atlantic City had enough in common, he said, but while Asbury Park in the last few years had transformed itself from a blighted, abandoned beach town into a “quirky, lovable place” by embracing its “shabby, eccentric” roots, Atlantic City remained trapped in the cycle of “flashy one-off ‘solutions’” like the Revel or, before that, the Borgata or, before that, Taj Mahal or before that the Trump Plaza and so on, ad referendum. Everyone had a theory on how to save Atlantic City, he said — less crime, a less depressing Boardwalk, more non-casino hotels. “But what you rarely hear is that Atlantic City needs Atlantic City itself.”

Doig’s essay was a refreshingly welcome perspective, and I agree with his conclusions, but Asbury Park was never an entertainment capital on the scale of Atlantic City, never required to be the economic engine for the region or provide big tax revenues to the state. In a weird way, the historical legacy that Doig and others have said Atlantic City should embrace has become the town’s worst enemy. Atlantic City’s status as fallen Queen of Resorts has allowed for a kind of shock capitalism that made it a free-for-all for development of the most cynical kind. Atlantic City post-1976 has been less a beach town than a factory town, its factories just happen to be arranged in a row beside its once-iconic Boardwalk. The fact that they happen to be in Atlantic City is largely irrelevant. The town’s most successful casino—the Borgata—sits out in the marshes atop what used to be the town landfill. It’s not really in Atlantic City at all.

All of which is to say that maybe the end of Atlantic City’s regional monopoly on legal gambling, and the great scaling-back of its casino industry that is taking place, might not be such a catastrophe for the region, especially if becomes the shock that kick-starts the town’s transition back to some version of itself at mid-century, a beach town with a gambling overlay, a mix of attractions with casinos as part of the picture.

Inevitably this change will mean pain for the town and the region. At its peak, the casinos employed anywhere from 45,000 to 50,000 people, but it’s hard to imagine the industry that never developed the Inlet, or many of the other neglected parts of Atlantic City, will be missed very much by the people who lived in those places, who watched their communities quietly errode in the glow of those absurd neon facades. Bill Terrigino and his neighbors were trampled on, shat out and laid off, all by the same industry that was supposedly saving them.

Despite what Reese Palley et al would have you believe, most of the development that accompanied the casinos—the suburban ranch houses, the burgeoning tax base—took place in the offshore townships, and those places are bracing for foreclosures, job losses and the reduction of services that come as the tax base falls. But even here maybe the apocalypse is not quite upon us. All that vacant beachside land, all that development and reuse potential, surely must have some positive economic aftereffects for the region—must mean service jobs, construction jobs for people in the county, who already provide such services in the neighboring beach towns.

Atlantic City’s days of attracting big-time investment from Wall Street banks or corporate gaming behemoths might be over, but maybe that’s not such a bad thing either. Kevin DeSanctis, the former Revel CEO, and Michael Garrity, who led development of the Revel project from within Morgan Stanley, took home a reported $7.1 million in 2013 for their role in midwifing a project that lost 95% of its value within two years. Maybe the end of the partnership of big banks, big corporations and friendly government agencies that kept Atlantic City in a zombie state for decades, while enriching itself, is a development that, in the long run, will be mourned by very few.

***

LAST NOVEMBER, A FEW WEEKS AFTER it won the right to buy the property at bankruptcy auction, Brookfield Asset Management backed out of its deal to buy the Revel, amid disputes with tenants and with the utility company that runs the onsite power plant that provides electricity to the property. The right to buy the Revel fell to Glenn Straub, a Florida real estate developer whom nobody had ever heard of, but who said he planned to spend $500 million to build a water park, a skiing and snowboarding mountain and a Revel university that would appeal, in words of The Wall Street Journal, “to‘geniuses’ looking to solve global problems like disease and nuclear-waste disposal.” Straub also dropped suggestions about a soccer franchise and a high-speed ferry that would bring visitors from Manhattan.

Bat-shit crazy? Yeah, it sounded like it a little, but no crazier than the last crew, and also, it’s worth pointing out, overwhelmingly favored by local residents in a Press of Atlantic City poll. And I’m guessing Straub, if he does buy the property, won’t lose 95% of his investment in two years. Anyway, I’m rooting for him.

In December, few weeks after the Brookfield deal fell through, Richard Stockton College of New Jersey, whose main campus is in the suburbs, but which got its start at the Mayflower Hotel in Atlantic City, bought the defunct Showboat for $18 million and announced plans to use the former casino as a new campus, with 852 student rooms, pledging its commitment to “spur economic development and community development in the city.” Then in December, Rowan University, whose main campus is in Glassboro, said it would locate a branch of its medical school in the city.

Meanwhile there was talk, at long last, of rezoning the beach blocks of Vermont Avenue and Rhode Island Avenue in the Inlet to allow for single-family residential development. Some of the LLCs that had spent years land-banking Inlet property had gone bankrupt and seemed keen to sell.

Who knows what impact these events will have on the health of Atlantic City and Atlantic County. I don’t think anyone expects them to replace the jobs lost through the closing of the casinos — at least not anytime soon. And even as the winds seemed to be shifting against them, a judge ruled in favor of the Casino Reinvestment Development Authority to use eminent domain to force the sale of one of the few remaining houses on Oriental Avenue. Still for the first time in a long time, it felt like maybe there was some faint cause for optimism.

***

THE HISTORIAN JOHN HALL, writing at the turn of the last century, (1899) noted that Absecon Island had always been “an attractive spot for refugees from war or justice.” Jeremiah Leeds himself had probably been one such refugee, fleeing his former Quaker coreligionists whose pacifistic sensibilities he must have offended by fighting in the Revolutionary War. But Atlantic City, through its heyday and well into its senescence, had always retained some of that outlaw element.

Nobody expects or wants an Atlantic City without gambling. It’s part of the town’s character. But the corporate gaming economy of the last few decades has been inimical to the sustenance of the community and its particular character, which was after all, the point of the exercise in the first place. And in the long run, it turned out, the industry’s failure to improve the town did no favors to the casinos themselves. One constant theme you hear from people who visit Atlantic City—and never plan to return—is that it’s creepy and depressing to drive to a billion-dollar casino-hotel through the corpse of a burned-out city.

***

WHEN I TALKED TO HIM last summer, Bill Terrigino had a new pirate flag, made from some heavy-duty fabric that had been used to tie down the dunes, but the black material had come unfastened during some storm and Bill had recovered it, cut it into sections and applied the Jolly Roger, making several new flags for friends and one for himself, which was now whipping violently over his front porch.

The vines growing all around his house had been grape vines, it turned out. I remembered reading something about Jeremiah Leeds’ plantation that described the grapes that had grown wild around the island. Somehow it struck me as a most alien image. Grape vines, in Atlantic City—how outlandish. But here they were all around the Terrigino’s house, covering it in fact.

The grapes were past their prime and starting to fall off the vine, staining the sidewalk. Bill picked a few and offered me one. I’d never eaten a grape off the vine before.

“Sweet as a kiss,” he said.

I hope he gets along with his new neighbors.

Excellent article

Interesting article, any new updates?